The brain on God

https://thenware.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-brain-on-god.html

Brain imaging reveals that spiritual experiences activate reward circuits.

Religious and spiritual experiences activate the brain’s reward circuits in a similar way to love, gambling, and music, a new study finds. Researchers used fMRI scans to look at the brains of 19 devout Mormons as they engaged in an experience described as "feeling the Spirit." This feeling was reproducibly associated with activation in nucleus accumbens, a critical region for processing reward and pleasure in the brain.

We spoke to the study’s senior author, neuroradiologist Jeffrey S Anderson.

ResearchGate: What motivated this study? Jeffrey Anderson: Billions of people make decisions based on religious and spiritual experiences. Such experiences are central to the maintenance of religious beliefs and convictions. Yet, despite how important these experiences are to people across faith traditions and cultures, we know almost nothing about how the brain participates in these experiences.

RG: What did you discover?

Anderson: In a group of devout Mormons, a spiritual experience they describe as "feeling the Spirit" is associated with activation in a reproducible network of brain regions. These regions include the nucleus accumbens, a critical region for processing reward and pleasure in the brain. We also found activation in attentions associated with perception of salience or novelty in the brain, and in regions that are associated with focused attention.

In one experiment, we had individuals press a button while watching audiovisual stimuli when they felt peak spiritual feelings. Activation in the nucleus accumbens spiked 1-3 seconds before they pressed the button, suggesting that there is a close relationship between spiritual feelings and brain reward activation. The centrality of reward in brain responses to spiritual feelings suggest that one view of religious training might align with classical conditioning, where association of positive feedback, music, and social rewards with religious beliefs or doctrines may lead to these doctrines becoming intrinsically rewarding. These same mechanisms may help explain attachment to religious leaders and ideals.

RG: How might these mechanisms play out in practice?

Anderson: Once you place religious experience in the context of brain reward circuits, it suggests that religious training can induce feelings of reward in response to doctrines or ideals or religious leaders. There's no reason one can't suppose that any doctrine from "love your neighbor" to "follow your leader" to "inflict violence on the out-group" might not be trained to induce reward. It may be that a Lutheran woman in Minnesota and an ISIS follower in Syria might experience the same feelings in the same brain regions for completely different belief systems, with very different social consequences.

RG: Can you briefly describe how you conducted the study?

Anderson: We obtained functional MRI images while showing the participants stimuli including prayer, readings of religiously-themed quotations and scripture, and audiovisual stimuli produced by the Mormon church designed to evoke spiritual feelings. After the imaging sessions, participants reported that the feelings they experienced during the scan were comparable to an intense worship service or private religious practice. Many were in tears after the scan.

We spoke to the study’s senior author, neuroradiologist Jeffrey S Anderson.

ResearchGate: What motivated this study? Jeffrey Anderson: Billions of people make decisions based on religious and spiritual experiences. Such experiences are central to the maintenance of religious beliefs and convictions. Yet, despite how important these experiences are to people across faith traditions and cultures, we know almost nothing about how the brain participates in these experiences.

RG: What did you discover?

Anderson: In a group of devout Mormons, a spiritual experience they describe as "feeling the Spirit" is associated with activation in a reproducible network of brain regions. These regions include the nucleus accumbens, a critical region for processing reward and pleasure in the brain. We also found activation in attentions associated with perception of salience or novelty in the brain, and in regions that are associated with focused attention.

In one experiment, we had individuals press a button while watching audiovisual stimuli when they felt peak spiritual feelings. Activation in the nucleus accumbens spiked 1-3 seconds before they pressed the button, suggesting that there is a close relationship between spiritual feelings and brain reward activation. The centrality of reward in brain responses to spiritual feelings suggest that one view of religious training might align with classical conditioning, where association of positive feedback, music, and social rewards with religious beliefs or doctrines may lead to these doctrines becoming intrinsically rewarding. These same mechanisms may help explain attachment to religious leaders and ideals.

RG: How might these mechanisms play out in practice?

Anderson: Once you place religious experience in the context of brain reward circuits, it suggests that religious training can induce feelings of reward in response to doctrines or ideals or religious leaders. There's no reason one can't suppose that any doctrine from "love your neighbor" to "follow your leader" to "inflict violence on the out-group" might not be trained to induce reward. It may be that a Lutheran woman in Minnesota and an ISIS follower in Syria might experience the same feelings in the same brain regions for completely different belief systems, with very different social consequences.

RG: Can you briefly describe how you conducted the study?

Anderson: We obtained functional MRI images while showing the participants stimuli including prayer, readings of religiously-themed quotations and scripture, and audiovisual stimuli produced by the Mormon church designed to evoke spiritual feelings. After the imaging sessions, participants reported that the feelings they experienced during the scan were comparable to an intense worship service or private religious practice. Many were in tears after the scan.

|

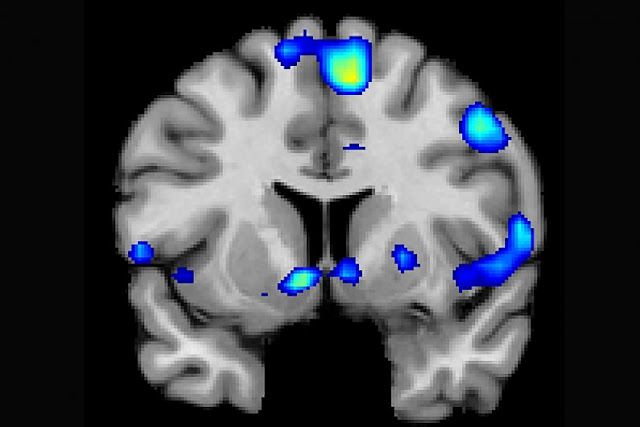

| fMRI scans recorded brain activity as devoutly religious study participants read quotes from spiritual leaders or watched religious imagery. University of Utah Health Sciences. |

RG: What was the most challenging aspect of the study?

Anderson: We were unsure how successful we would be at reproducing sincere spiritual experiences in a laboratory setting. Although an MRI scanner can be loud and artificial, it is also a private place where people can be alone with their thoughts and feelings. We were surprised at both how intense our volunteers reported their experiences to be and how reproducible the identified brain network was. This was replicated independently in four separate experiments.

RG: Why did you select Mormons? Do you think the brain reward could differ across religions?

Anderson: We chose Mormons because of the centrality in their theology and practice of charismatic spiritual feelings. It can't be overstated how important these feelings are to devout Mormons. They report experiencing these feelings frequently, and our volunteers had each served 1-2 year missions in which recognizing their own thoughts and feelings when they were "feeling the Spirit" was a daily activity.

We don't know how similar the experience of spiritual feelings is across different religious groups, but there are good reasons to expect that a similar library of brain responses may be shared across cultures. A similar region to the one we observed was seen in a study involving prayer in Danish Christians. Other early studies suggest a key role for brain reward centers in religious experience

RG: Could this feeling be reproduced in people who are not religious? Are there comparable non-religious feelings?

Anderson: I believe that feelings associated with patriotism and nationalism will show tremendous similarity in brain responses to ecstatic religious experience. Anecdotally, people who are not religious use similar language to describe feelings associated with peace and joy when in nature or contemplating profound ideas about science. We know that similar regions are activated during appreciation of music, experience of romantic and parental love, and winning at gambling.

Anderson: We were unsure how successful we would be at reproducing sincere spiritual experiences in a laboratory setting. Although an MRI scanner can be loud and artificial, it is also a private place where people can be alone with their thoughts and feelings. We were surprised at both how intense our volunteers reported their experiences to be and how reproducible the identified brain network was. This was replicated independently in four separate experiments.

RG: Why did you select Mormons? Do you think the brain reward could differ across religions?

Anderson: We chose Mormons because of the centrality in their theology and practice of charismatic spiritual feelings. It can't be overstated how important these feelings are to devout Mormons. They report experiencing these feelings frequently, and our volunteers had each served 1-2 year missions in which recognizing their own thoughts and feelings when they were "feeling the Spirit" was a daily activity.

We don't know how similar the experience of spiritual feelings is across different religious groups, but there are good reasons to expect that a similar library of brain responses may be shared across cultures. A similar region to the one we observed was seen in a study involving prayer in Danish Christians. Other early studies suggest a key role for brain reward centers in religious experience

RG: Could this feeling be reproduced in people who are not religious? Are there comparable non-religious feelings?

Anderson: I believe that feelings associated with patriotism and nationalism will show tremendous similarity in brain responses to ecstatic religious experience. Anecdotally, people who are not religious use similar language to describe feelings associated with peace and joy when in nature or contemplating profound ideas about science. We know that similar regions are activated during appreciation of music, experience of romantic and parental love, and winning at gambling.

|

| Several brain regions become active when devoutly religious study participants reported having a spiritual experience, including a reward circuit, the nucleus accumbens. Credit: Jeffrey Anderson |

RG: Is it possible that some people could be more prone to being affected by religion in this way than others?

Anderson: This is very likely. In our study, we found that some brain regions were more active in some individuals than in others. For example, activity in the insula during spiritual experiences varied across individuals, and these differences in activity correlated with moral values reported by those same individuals in questionnaires after the study. We expect that the differences from individual to individual may tell us about how different people and groups may differ in their perception of spiritual feelings.

RG: What was it like working with the volunteers?

Anderson: We appreciate the willingness of our participants to share their time and feelings. It can be intimidating and vulnerable to allow deeply held beliefs to be studied, and their courageous involvement made our study possible.

Featured image courtesy of flickr.

Anderson: This is very likely. In our study, we found that some brain regions were more active in some individuals than in others. For example, activity in the insula during spiritual experiences varied across individuals, and these differences in activity correlated with moral values reported by those same individuals in questionnaires after the study. We expect that the differences from individual to individual may tell us about how different people and groups may differ in their perception of spiritual feelings.

RG: What was it like working with the volunteers?

Anderson: We appreciate the willingness of our participants to share their time and feelings. It can be intimidating and vulnerable to allow deeply held beliefs to be studied, and their courageous involvement made our study possible.

Featured image courtesy of flickr.

First, functional MRI is a very bad tool for recording such experiences. The loud noises due to field gradient pulses is distracting. (I was an MRI physicist and I know whereof I speak.) The statistical methods used to analyze fMRI have been criticized. Second, studies showing the effects of meditation and differences between religious and non-believers, using SPECT scans, have been reported much earlier by Newberg; see "Are we hardwired for faith" at

ReplyDeletehttp://rationalcatholic.blogspot.com/2014/03/are-we-hard-wired-for-faith-religious.html